The Path Leads Into Nature With Nils Faarlund

Nils Faarlund is a legendary Norwegian eco-philosopher, mountaineer and a great friend of nature. We spoke to him about the Norwegian term for outdoors life, Friluftsliv, natural materials and design.

# How would you explain the Norwegian term friluftsliv to English speakers?

In my opinion, outdoor activities in modern societies are responses to the stress, boredom and effort for building identity caused by an urban lifestyle.

Norwegians struggling for national freedom in the 19th century found the worldview and values of The Romantic Movement appealing. The Romantics were inspired by traveling in mountain terrain – not as sportive activities, but as an encounter with free nature and the noble savages of the valleys of the Alps who were unspoiled by the industrial revolution in the European plains, leading their life in an intimate dialogue with their homeland.

In the 20th century the Norwegian tradition of encountering free nature in the mountains diversified to the woods, lakelands and the sea. Referring to the historical events of the 19th century, we can say that for 9 out of 10 Norwegians, this pastime which we enthusiastically name friluftsliv, is a way of embodying the inherent value of free nature as well as human worth and dignity.

# We met for the first time during a seminar on Green Growth. Is it possible to combine nature conservation with economic growth?

If we use the term green to replace nature friendly, and understand growth as the maturation growth in - for instance a birch tree, I’m with you. Still I insist on using the term free nature to express that nature has intrinsic value.

As long as we allow limitless growth to be an ideal in the society of modernity, the adjective green is really nothing else than cosmetic camouflage. Allowing society to be ruled by the principle of quantifiable growth in the form of GNP is breaking of the tolerance limits of free nature.

It is an irrefutable fact that free nature cannot be produced. Neither can the natural condition be recycled. The idea that economic growth, as expressed globally today, is compatible with nature conservation is a deep misunderstanding. Incidentally, nature conservation is already long ago a too defensive attitude:

Nature friendliness is the way!

# What is your experience of the development of the last years with regards to the use of mobile technology? Is there any path back to silence and presence from where we have come?

It looks undeniably dark with the vital presence and silence. These days it’s not far between those who roam both the streets and free nature with cords hanging out of their ears. It doesn’t look like the growth of that phenomenon will decline any time soon. But all the growth curves of modernity’s trend activities have one thing in common, they culminate.

Back in the early 90’s I got the mission to do a study of the meaning of silence for the Norwegian Environmental Directorate. The results ended up as the most popular report in the Directorate. Silence was a subject in Norwegian media for a long time afterwards.

Even if in daily life, it can be discouraging to see the large flock of the lonely, silence is not a term to be joked around with. And even if Norwegians are often pretty loud in their outdoors life, there are occasions where silence gets its place. My contribution in finding words to describe what lives in silence:

Silence is a way that free nature speaks to us by keeping quiet.

From the legendary cabin of philosopher Arne Næss’ hytte at Tvergastein (1505 m a.s.l.) Photo: Ingebjørg Nordby Seim.

# How important is it to acquire a language that is close to nature to understand the universe?

After having been concerned with the ‘purposeless’ encounter with free nature – in accordance with the Norwegian tradition of friluftsliv for half a century - I still hold that :

Nature is the Home of Culture

In the part of the Universe that we can relate to with our senses, we can also feel at home. As humans we have developed a remarkable ability of language that helps us to share experiences and collaborate in understanding both the small and great contexts of life. As Einstein said, abstract thinking – removed from reality – runs short when exploring the secrets of nature. In his opinion, we can only get there with experience made with empathy, interpreted with intuition.

Parenthetically, I prefer pattern recognition thinking rather than intuition, which is really to loose after the New Age movement conquered this term. Again, Einstein warns us in believing that the way of logic – that is the language of abstraction – is of help. No, we need a language that is close to nature, because:

The language is the tool of thought – if the words are dull, the thoughts are dull

In Norway we are lucky to have had countrymen who made haste slowly during the industrial revolution. That spared Norwegian nature. Not only that, but a language that has been made in cooperation with the ‘noble savages’, with a diverse and demanding nature, still gives us the best opportunities to find nature-friendly ways of life.

# You are known for you love for traditional mountain gear. What would you like to tell the new generation of designers who create clothing and equipment for the future?

I meet them with Gandhi’s question:

Do you want to be part of the problem, or of the solution?!

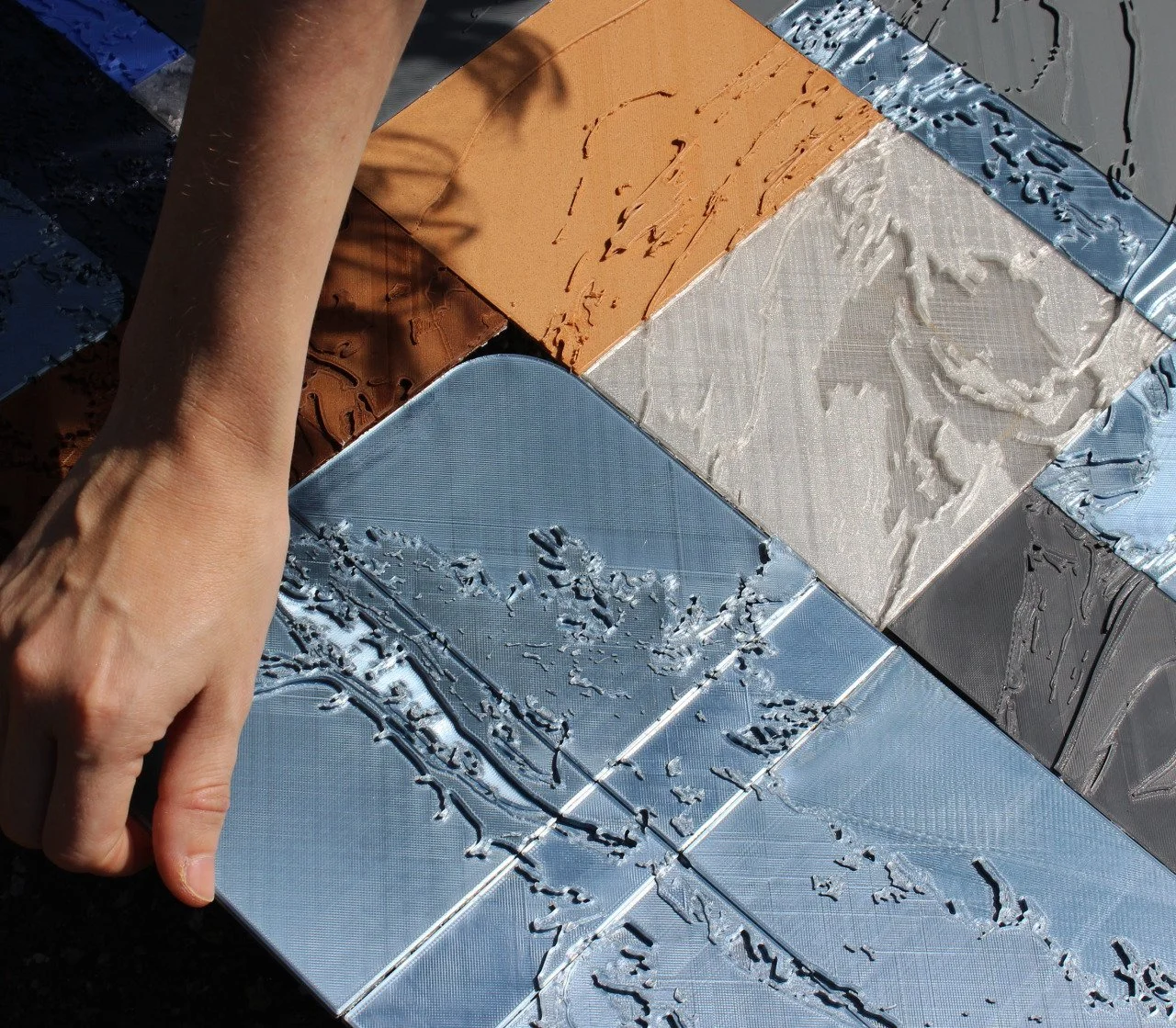

Seen with the eyes of modernity, the gear I hold on to is really antiquated, or more diplomatically expressed, classical. Since nature will never go out of fashion, we can learn a lot from the material choices and design of previous generations.

A good example is the British cotton quality Ventil and rainwear made of quality cotton impregnated with natural waxes and oils – for instance Barbour. The ski design of the generation of Sondre Nordhem (Norwegian skiing pioneer b. 1825), is another example of timeless design and material choices.

Wood is an irreplaceable material in making skis – all skis of outstanding quality have a wooden core. You will also have to search far and wide for a solid that provides better glide on snow than wood does. The word ski means a long, thin piece of wood. When holding on to using natural fibres in clothing for friluftsliv and outdoor activities, it is to be part of the solution, in the context of Gandhi’s statement. Having tried out synthetic fibres in my time as an engineer, I haven’t suffered one day as a result of valuing natural fibres.

# What can designers learn from nature – and from the Norwegian tradition of friluftsliv?

The most admirable proof of what designers have learned from free nature in this country is to be found in the field of shipbuilding. Already in the Viking Age. As can be seen in the magnificent ships conserved in the museums, the skills in material choice and design had reached an impressive level.

Along the long Norwegian coast these skills have been further developed and adapted to local conditions and use. The process starts with choosing the material in the woods, continues with the material processing, discriminating craftsmanship, experiential learning from the use and an exemplary end of the time in use – all without burdening free nature.

Skiing is an equally impressive example, albeit not as immediately noticeable as a wooden boat. When using equipment while seeking to embody the traditional values of Norwegian friuftsliv, there is hardly a situation where synthetic fibre offers any advantages over the natural. This gives clear guidelines for the manufacture of clothing and gear even in other fields. There is a lot to be learned from life out of doors – that is to say, not the activities that are sportified and goal-oriented, but when in free nature our intention is being and learning.

# Being a man of nature, can you provide some examples from the cultural sphere that has inspired your work?

Early on, when Henry David Thoreau’s Walden was published in Norway in the 1950’s under the name “Life in the Forests” a hundred years after its publishing date in the US, I immediately understood that this was something for me. I devoured books in many different genres, but this was the book above all others. I bought the book with shirtingbind (a tightly woven cotton fabric) using money I earned while helping out during the potato harvest. Thoreau was a big inspiration for me to start The Norwegian School of Mountaineering in 1967 to win friends for free nature. When I recently wrote the book Friluftsliv – a formative journey I ended with a quote from Walden:

In Wildness is the Preservation of the World

When encountering free nature, we acquaint ourselves with nature. Acquaintance commits us for nature friendly ways of life and to help changing the world joyfully.

The list of thinkers who have inspired me after I left my career as a researcher in microbiology and biochemistry in 1967, is long. Closest to Thoreau is the philosopher Spinoza that, thanks to my fellow mountaineering rope mate professor Arne Naess discourses, has provided values anchoring for my thinking and action at work.

Gandhi was also an early guide in the art of being a part of the solution, a way of thinking that rhymes with Einstein’s reminder that the problems that the modern way of life has led to, are not solved by thinking in the way that has caused the misery in the first place. Since the core of my work has been about making learning happen in the encounter with the potential life dangers of free nature, other important references have been Jean Jacques Rousseau, Martin Buber and our own Hans Skjervheim (Norwegian philosopher 1926-1999) - in embodying the intrinsic value of free nature and human dignity.

(The interview was done originally in Norwegian and was translated with the kind help of Nils Faarlund)

Elementa Conversations: